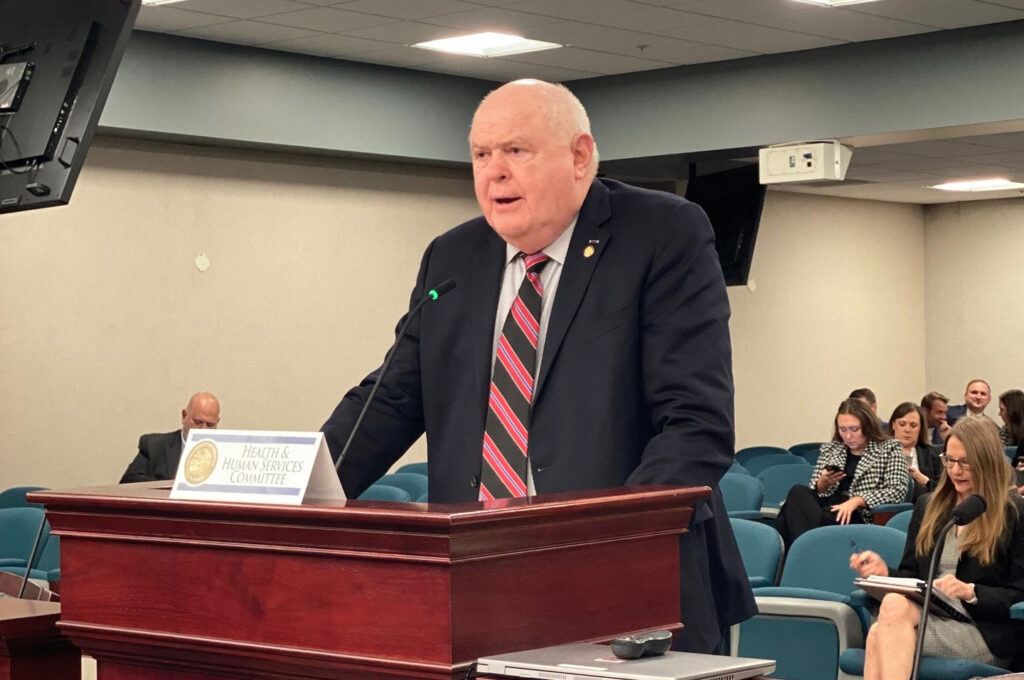

Established in 2012 by then-Judge Patt Maney, Okaloosa County’s Veterans Treatment Court helps former service members overcome trauma and addiction through a unique combination of accountability, treatment and peer support.

- In a county deeply connected to the military, Judge Angela Mason now presides over a program that maintains an 89-92% success rate by addressing the complex needs of veterans who find themselves in the criminal justice system.

“Veterans will come back from service and find themselves in what I call a moment in time they can’t get out of,” Mason said. “They’ve seen things you can’t unsee. They’ll receive an injury, maybe get addicted to a substance and can’t figure out how to get off of it.”

The voluntary 12-18 month program combines court supervision, VA services, and veteran peer mentoring to help participants address underlying issues like traumatic brain injury, PTSD and substance abuse. Unlike traditional court, the program takes a holistic treatment approach while maintaining military structure and values.

“What we have found is once people get to the point that they need us, it’s such a cycle they can’t get out of,” Mason said. “The holistic approach helps address all those issues at the same time and really lets the veteran recognize how those issues are working together.”

Taking over the program from Judge Maney proved daunting initially for Mason.

- “While it’s always intimidating to do anything after Representative Maney, he left the program so well that he made it easy for me to navigate,” Mason said. “It’s different because I don’t have the military experience that he did. But my father was in the Navy and my grandfather served, so I had that built-in respect for the military that so many of us do.”

Maney’s continued support proves invaluable. “To this day if I’m having a moment where I just don’t really know what to do, he’s always open to my phone calls,” Mason said.

The court’s success stories illustrate its impact. One involved a World War II veteran George who entered the program homeless and struggling with alcoholism. Through the court’s intervention, he found sobriety and reconciled with his estranged family before passing away.

Another case demonstrated the program’s commitment to justice and rehabilitation. A defendant who unknowingly became a convicted felon through an earlier plea deal entered Veterans Treatment Court on a probation violation. During his two years in the program, his growth and genuine misunderstanding of the original plea led the state to allow him to withdraw the plea, removing the felony conviction while still holding him accountable.

- “When he graduated and recognized what the system had done for him to save his life, he cried, we all hugged,” Mason said. “That’s not something I usually see in court. It was really heartwarming.”

Participants progress through five phases, starting intensively with twice-monthly court appearances and frequent treatment sessions before gradually stepping down supervision as they demonstrate stability. Throughout the program, veteran mentors – often graduates themselves – provide crucial peer support.

“Those in the military have done things that I cannot relate to,” Mason said. “With the veteran mentor program, they have people who have been exactly where they’ve been, and they can understand the conversation better than someone like me who hasn’t been there.”

Mason emphasizes this is no easy path. The most challenging aspect comes from balancing the rule of law with the program’s holistic approach. While the vast majority succeed, those who don’t face consequences.

- “They always say you can’t help people who don’t want to help themselves,” Mason said of difficult cases. “When people try to manipulate a program that is designed to help, it puts a negative spin on the program or makes it look like we’re just an easy pass for veterans. And we are absolutely not.”

Success manifests in various ways beyond graduation rates. Mason measures it through watching transformations unfold.

“I can see the light switch go on for many of the veterans when they realize that the court is not there to hurt them but that this is the treatment they need,” Mason said. “I really enjoy graduating the people who don’t want to be here in the first place. When they figure out that they do need it and then at graduation say, ‘Judge, I did not like you in the beginning, but now I am grateful.‘”

The court holds graduations four times annually, with six to 11 participants typically completing the program in each class. Upon graduation, charges may be dismissed or probation terminated based on the specifics of each case. The most recent graduation was at the end of October and featured Shalimar Mayor Mark Franks.

“I want to say how proud I am of each one of you,” said Mayor Franks in his remarks to the graduates. “You have shown resilience, discipline, and dedication—qualities that we as a community deeply respect. You have overcome and you will continue to thrive.”

The program continues evolving, recently expanding to include DUI cases. Mason focuses on educating local attorneys about the program’s benefits while maintaining its rigorous standards. She speaks regularly to legal groups about the court’s mission and impact.

- “Sometimes people think it’s either a free pass, which it is not, or that it’s going to be too hard and too much extra work,” Mason said. “But sometimes people need the extra work. Otherwise I’m going to see them again in a year on the same kind of charge.”

Hundreds of veterans have completed the program since its inception. Many graduates return to support and mentor others, creating an ongoing cycle of recovery and service that reflects the military values at the program’s core.

“What the treatment court does for the veteran and for the community is it helps people recognize why they are committing a crime, what led them here in the first place, and hopefully helps them figure out a path through it,” Mason said. “I have seen people come into this program broken and now serve as mentors to help other people who need it. The program is so much more than just a treatment court. It really is a way to help make not only those individuals, but the community as a whole better.”